I felt honored to be interviewed by Lauren Cerand for Pen America's Pen Ten series.

- By: PEN America

- PUBLISHED ON DECEMBER 9, 2014

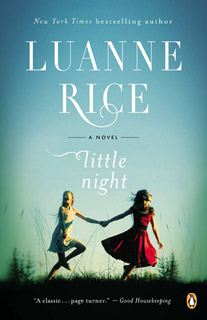

The PEN Ten is PEN America's weekly interview series curated by Lauren Cerand. This week Lauren talks with Luanne Rice, theNew York Timesbest-selling author of 31 novels, which have been translated into 24 languages, including The Lemon Orchard, Cloud Nine, and Dream Country.

When did being a writer begin to inform your sense of identity?

From as far back as I can remember. As a child I wrote poems about nature and stories about people with secrets. As a child I could look out my bedroom window and see the Children’s Home on top of the next hill. We went to school with kids who lived there. There was one boy I wanted us to adopt, but our family had our own sorrows, and my parents said it wasn’t possible. I remember crying that night, and instead of sleeping I wrote a story about a boy with freckles and a hole in his sweater.

Whose work would you like to steal without attribution or consequences?

The idea of stealing another's work is horrifying to me. Writing is the closest thing to sacred I know.

Where is your favorite place to write?

By a window with cats on my desk.

Have you ever been arrested? Care to discuss?

I’ve never been arrested, but as a teenager I was accused of vandalism. A state trooper came to my house late at night. It was frightening to be accused of something I hadn’t done, and to feel I wasn’t being believed.

Obsessions are influences—what are yours?

Coastal New England, factory towns, Chelsea prior to gentrification, sisters, fathers, love, immigration. I’ve gone to Ireland to stand on the docks and commune with the family ghosts. I have Mexican friends living undocumented in LA. One woman was trafficked, and she is traumatized and can’t go anywhere for help because she fears getting caught without papers, and she fears the coyote who imprisoned her will come after her or take revenge on her family.

What’s the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words?

In my first novel I wrote about growing up with an alcoholic father. I had been tempted to censor myself, but somehow I didn’t. I wound up being disowned by some members of his family, and at my first-ever reading—at the New Britain Public Library, in my home town—a friend of his stood up and said he was glad my father was dead so he didn’t have to read what I’d written.

What is the responsibility of the writer?

To tell a story.

While the notion of the public intellectual has fallen out of fashion, do you believe writers have a collective purpose?

Yes, I feel it strongly. At this year’s Chicago Tribune’s Printers Row Literary Festival I sat on a panel with Luis Alberto Urrea and Cristina Henriquez. It was powerful for me—they have written wonderful books about immigration, and I felt honored to join my voice with theirs. Luis is a kind of spirit guide for me. I keep his book about death on the border, The Devil’s Highway, close to me, on my desk. Before writing The Lemon Orchard, I asked him if it was okay for me to write about illegal immigration because it’s not, literally, my story. I’d never worried like this before—I’ve always written from my heart and obsessions, written what I dreamed and felt. But in this case I was writing about people crossing the border, dying in the desert or living in fear, undocumented in Boyle Heights, and it was inspired by real families and actual events. I worried that this story wasn’t mine to write. But Luis told me that not only could I write it but that I must. I felt tremendously supported.

What book would you send to the leader of a government that imprisons writers?

Freedom in Exile by His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

Where is the line between observation and surveillance?

Observation is gentle, surveillance is brutal.